February 12th, 2026

“Why is it that when one man builds a wall, the next man immediately needs to know what’s on the other side?” – George R.R. Martin

Walls as metaphors have earned a bad reputation in recent years, and not without reason. But unlike walls meant to keep others out, the fourth wall can be understood as a conceptual boundary that turns the “players” inward. It is an invisible line separating the performers from the “real” world, clearly dividing the watcher from the watched. Traditionally, the fourth wall has been framed as a mechanism for suspending disbelief, and largely utilized to pull the viewer into the action on stage. Its value, however, has almost always been defined in terms of how it can benefit the audience.

We see this logic mirrored across contemporary media platforms too, where performance is increasingly accompanied by a low, persistent plea: like it, please?; subscribe, please?; just LOVE ME, please?… Here, worth is calculated through attention, clicks, approval, and applause, as if the meaning within a performance and the person behind it, can only be validated from the outside. But what if that paradigm were reversed? What if performance were valued not as a product shaped for consumption, but as a trace of the performer themselves? A way of seeing inward, rather than performing outward?

But how might this align clinically, and what value might the flipped orientation offer? As with the creative work of others, I notice recurring elements and themes throughout my own body of work, undercurrents of my wiring and lived experiences that surface again and again in the material I create. The psychological foundations of these choices are largely unconscious in the moment of creation, yet each piece carries an imprint of my neurological patterns and quite often, my neuroses at the time each piece was created. More than that, works can reveal how I organize thought, how I perceive relationships, even how and where I hold tension in my body, tension that inevitably shapes the movement I craft for others. So what if we encouraged our students and clients to experience their own creative work with similar insight?

I have always felt an affinity for the Romantic ballets, sublime narratives steeped in social exclusion, unrequited love, and the supernatural. If ballet were ever gothic, it would be in the Romantic era. While thinking about this piece, I couldn’t shake that period (I’ll blame St. Valentine): a brief yet consequential moment that unfolded alongside the first Industrial Revolution, when machines began replacing human labor and the social order trembled under the weight of change. The upheaval of the time: political, economic, existential, reshaped not only industry but human consciousness itself.

It is no coincidence that Romanticism turned inward. As the external world grew increasingly unstable, artists retreated into emotion, imagination, and the sublime. Around the same time, Auguste Comte emerged, founding what we now call sociology and insisting that we must “know ourselves to improve ourselves.” Convinced that the turmoil of the age could be addressed through the study of human behavior, Comte connected solutions to social disorder to the self. The only way out, he believed, was in.

The fourth wall can be understood in a similar way. Rather than merely a device for audience immersion, it becomes a threshold that protects the space of inward inquiry. It allows the performer to turn toward their own psychological terrain without immediately converting that exploration into a bid for approval. In this sense, the wall is not exclusionary but protective, a boundary that makes introspection possible. What appears, from the outside, as separation may in fact be a necessary condition for depth.

Artists compose with sound, movement, words, and paint. We have been conditioned to associate composition with sophistication or innovation, evidence of an individual artist’s brilliance that is measured against others. But perhaps it is time to understand composition differently, not as a display of superiority, but as a reflection of the human who created it. What we compose may, in fact, reveal how we are composed.

In an increasingly uncertain and disorienting world, turning inward is not a retreat, it is a reckoning. Through creative expression, across forms, we are given the rare opportunity to witness ourselves more truthfully. Art becomes not performance for approval, but observation of the self.

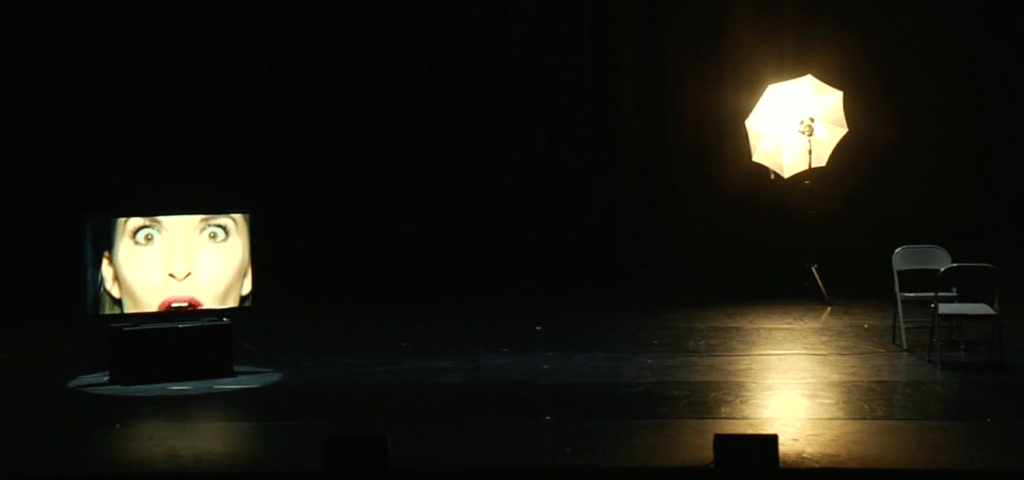

Link: Feed (excerpt) created in collaboration with Meredith Howard and Stefan Colson, and Hanon Rosenthal. Image: The Desperate Man; by Gustave Courbet, 1843, by Gustave Courbet